LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN'S ANNOTATED COPY OF SCHLICK ON ETHICS

LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN'S ANNOTATED COPY OF SCHLICK ON ETHICS

[WITTGENSTEIN, Ludwig (1889–1951) – his copy], SCHLICK, Moritz (1882–1936)

Fragen der Ethik

(Julius Springer, Vienna), 1930 [first edition]

8vo; pp. 152, vi, [2, ads]

Wittgenstein’s copy of Moritz Schlick’s book on ethics, with annotations that reveal a profound shift in his philosophy. The only known example of Wittgenstein’s marginalia in a philosophical work.

The book was sent by Schlick to Wittgenstein at Trinity College, Cambridge, in the autumn of 1930. Wittgenstein read the book, making his marginal notes, before writing to Schlick in November 1930, warning him ‘I think I won’t agree with you on a lot of things’. In December of that year Wittgenstein travelled to Vienna to discuss philosophy with Schlick and Friedrich Waismann. These conversations were recorded, and we know that Wittgenstein repeated some of the comments he had made in the margins.

Most strikingly, Wittgenstein writes ‘Das ist die tiefe Fassung!’ next to Schlick’s statement of Plato’s famous ‘Euthyphro Dillema’ (Is the good loved by the gods because it is good, or is it good because it is loved by the gods?). With these five words – ‘That is the deeper formulation!’ – Wittgenstein sets himself against Socrates, against Schlick and the Vienna Circle, and against traditional metaphysics. The ‘deeper formulation’ referred to is simply ‘What God commands, that is good’. This, Wittgenstein told Schlick shortly after receiving the book, ‘cuts off the way to any explanation “why” it is good’, and rules out any ‘theory’ of ethics at all.

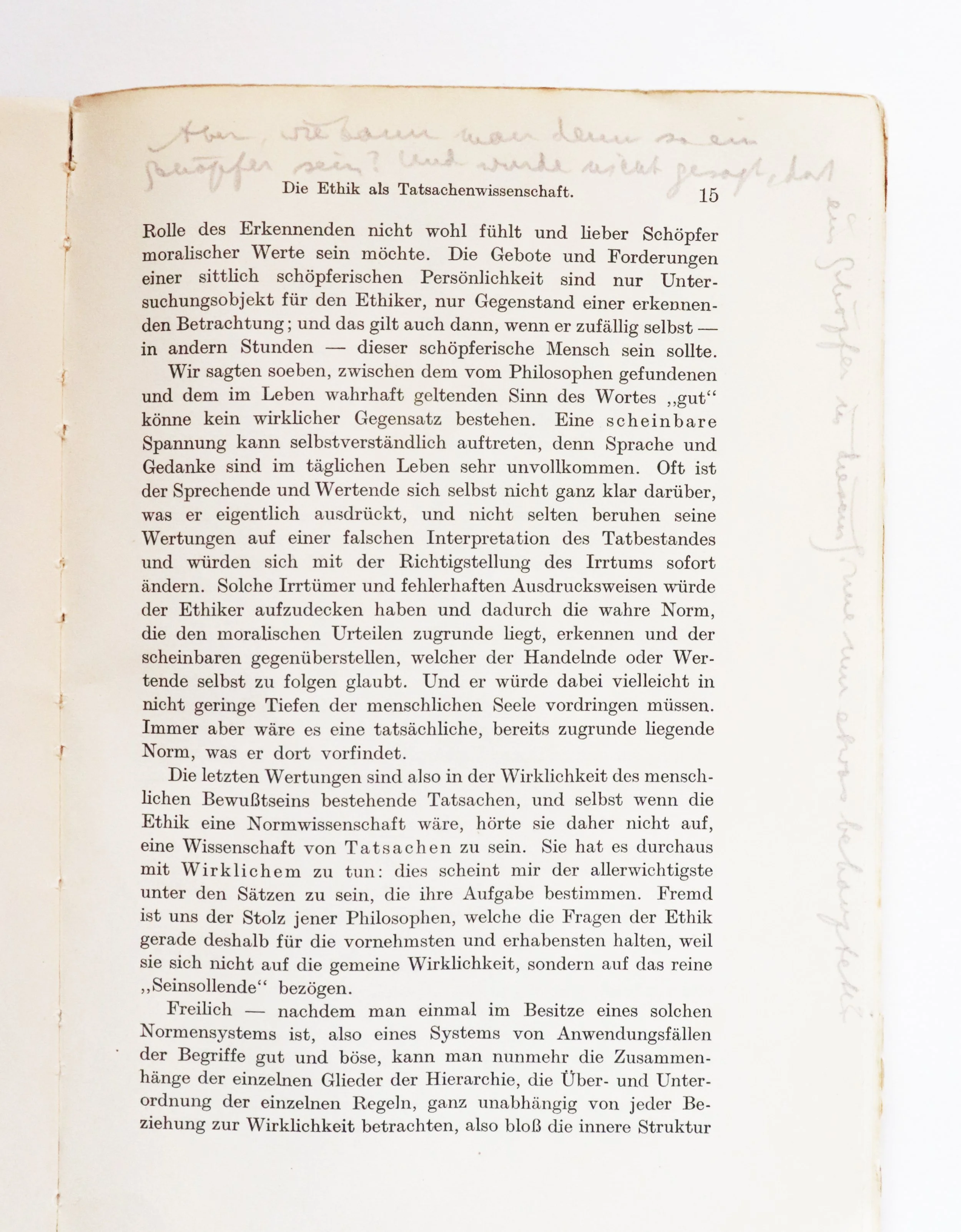

But where the Wittgenstein of the Tractatus ‘remained silent’ on ethical questions, here Wittgenstein pursues the ‘deeper formulation’, arguing with Schlick in the margins about the work of moral philosophy. In Schlick’s section on ‘Ethics as a Factual Science’, for example, Wittgenstein exclaims ‘Wie seltsam aber, daß dieses Mißverständnis vorkommt!’ [‘How strange that this misunderstanding should occur!’] when Schlick argues that the moral philosopher errs in finding a discrepancy between ethical values and human nature. And when Schlick elaborates on this idea, saying that in this error the philosopher becomes a ‘creator’ of morals, Wittgenstein again interjects: ‘Aber, wie kann man denn so ein Schöpfer sein?’ [‘But how can one be such a creator?’]. Expanding on this, Wittgenstein rightly notes that Schlick had earlier used the term ‘Schöpfer’/‘creator’ for someone who simply ‘asserts something’ (‘Und wurde nicht gesagt, daß ein Schöpfer in diesem Sinne nur etwas behauptete?’).

That Wittgenstein read this section carefully is especially significant, because it is here that Schlick develops his idea of philosophical ethics as a ‘game’. These notions, of the ‘creation’ of values, and of ethics as a ‘game’ are central to our understanding Wittgenstein’s development: it is precisely the relationship between the active ‘making’ of meaning and the systematic application of rules in the form of ‘games’ that characterises the shift in his philosophy in the years 1929/1930.

The exact status of Wittgenstein’s position vis a vis the ‘deeper formulation’, then, is of the greatest relevance to understanding Wittgenstein’s ‘transitional’ philosophy, especially in light of Stanley Cavell’s groundbreaking studies in the 1970s. The marginal notes here differ in important ways with what Wittgenstein wrote even as late as his ‘Lecture on Ethics’ of 1929. With regard to Schlick’s work the issue is especially pointed: in many ways Schlick’s call for a ‘scientific’ ethics would appear to fit with Wittgenstein’s skepticism about ethical ‘theory’. Yet here is Wittgenstein arguing violently against Schlick’s positivism – contending that the ‘deeper interpretation’ must be a rule-based, arbitrary ethics and also questioning whether the philosopher who moralizes can act as a ‘creator’, and in what sense ‘creation’ relates to assertion and to the ‘misunderstanding’ inherent in ethical philosophy. This is all consistent with Cavell’s interpretation of Wittgenstein’s later philosophy – that is, with a very strong emphasis on the ethical component of Wittgenstein’s nominalism, and the rejection of traditional theories of meaning (including the theory given in the Tractatus).

Elsewhere Wittgenstein marks the margins and underlines, and makes an extended comment at the end of the book. The latter has never been published or publicly analysed, though it is discussed by Rush Rhees in a typescript offered with the present book. Rhees was probably the first owner of the book after Wittgenstein (see provenance note below).

In purely biographical terms the volume is no less important. In 1926 Wittgenstein had stopped teaching and returned to Vienna. There he had been coaxed back to philosophy by Schlick – the unofficial leader of the ‘Vienna Circle’ of logical positivsts. Schlick and Wittgenstein developed a respectful relationship (‘Each of us thought the other must be mad’, Wittgenstein told his friend Paul Engelmann), and soon Wittgenstein was invited to informal meetings of the Vienna Circle. Although Wittgenstein increasingly set himself against the strictly analytical position of the Circle, this was a decisive period for him: in 1929 he returned to Cambridge, and, in the fullest sense, to philosophy.

From Cambridge, Wittgenstein remained in close contact with Schlick, and in 1929 visited him in Vienna to begin a series of semi-formal meetings between the two men and Friedrich Waismann, so that Waismann could complete a book that would serve as the Vienna Circle’s ‘introduction’ to the Tractatus. It is in these conversations that Wittgenstein began to formulate the ideas that he would develop into the work finally published as Philosophical Investigations.

Fragen der Ethik was published in the autumn of 1930, and Schlick quickly sent the present volume to Wittgenstein in Cambridge – it is probably one of the 12 author’s copies he is known to have recieved from Springer. Wittgenstein’s reading and annotation have a sense of immediacy about them, and we can infer that he had already read what he needed (some parts remain unopened) before writing to Schlick on 27 November 1930 (‘I think I won’t agree with you on a lot of things’). Certainly the annotations predate Schlick’s meeting with Waismann on 17 December at the family summer house on the outskirts of Vienna, because there Wittgenstein expounded on some of the points raised in the marginalia, in fact repeating some of the annotations verbally. These conversations were edited by Brian McGuinness and published as Ludwig Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle (Blackwell, 1979); in that book use is made of the marginalia in the present volume (see below for provenance).

Again, the moment of reading is decisive: it is in the context of Wittgenstein’s conversations with Schlick and Wiasmann that we first hear about ‘tools’ and about ‘games’, about the profundity of the ‘shallow’ answer to Euthyphro’s Dilemma, and about the nature of ‘creation’ in ethical philosophy. Andreas Vrahimis has recently argued that Schlick’s Fragen der Ethik had a strong influence on the development of Wittgenstein’s thought: here, in the margins, is the evidence for that claim.

Philosophical material in Wittgenstein’s hand is notoriously scarce: we can find no other evidence a philosophical book annotated by Wittgenstein (see note below). Very few letters to have been offered for sale have contained philosophical writing.

Fragen der Ethik, published in English translation in 1939 as Problems of Ethics, is, in its own right, an important work by a philosopher whose career was tragically cut short when he was murdered by a former student in June 1936. Aside from his as leadership of the Vienna Circle, and his role in bringing Wittgenstein out of the wilderness, Schlick’s own ideas are undergoing a revaluation. He was an early philosophical interpreter of Einstein (who admired and corresponded with Schlick), and has been situated on the ‘right wing’ or ‘cultural’ side of logical positivism. This is one of the very few works from the Vienna Circle to deal in any way with ethical questions.

Provenance: Rush Rhees, Wittgenstein’s friend, pupil and literary executor. Included is a short typescript by Rhees (in German), concerning the book and Wittgenstein’s annotations.

Condition: Fair condition: covers worn, spine chipped at top and bottom; front hinge loose; title page adhered to front cover and somewhat torn, otherwise internally very good, noting only Wittgenstein’s marginalia; housed in a custom made cloth case with gilt spine label. Professional conservation work on the title-page in June 2025 revealed a small amount of an ink annotation; this is likely Schlick’s dedication to Wittgenstein, though it proved impossible to reveal the whole inscription.

References:

Stanley Cavell, The Claim of Reason (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979)

Russell B. Goodman, ‘Wittgenstein and Ethics’, Metaphilosophy 13 (1982), pp. 138–148.

Brian McGuinness (ed.), Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle: Conversations Recorded by Friedrich Waismann, trans. Joachim Schulte and Brian McGuinness (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1979), pp. 115–1117, where the present volume is referenced directly.

Friedrich Stadler (ed.), Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle: 100 Years After the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (Cham: Springer, 2023)

Suzanne Stern-Gillet, ‘Schlick’s “Factual Ethics'“, Revue Internationale de Philosophie 37 (1983), pp. 145–162

Andreas Vrahimis, ‘Schlick and Wittgenstein on games and ethics’, Philosophical Investigations. 47 (2024), pp. 76–100.

A note on Wittgenstein’s books: LW’s copy of a text on hydrodynamics has recently come to light. Some of his books went via Russell to McMaster University, though these are not annotated. LW’s annotated copy of Hardy’s Course of Pure Mathematics is now lost. His (unannotated) copy of Heine is at Trinity College Cambridge. A copy of the journal Erkenntnis with a marginal accusation of plagiarism by Carnap was exhibited in 2015 at the University of Vienna. Kotte Autographs are offering a lightly annotated copy of an offprint on Goethe's ‘Theory of colours’. We find no copies of Wittgenstein’s books at the von Wright and Wittgenstein Archives.