A LARGE PAPER COPY OF WILKINS' 'ESSAY', THE MACCLESFIELD COPY

A LARGE PAPER COPY OF WILKINS' 'ESSAY', THE MACCLESFIELD COPY

WILKINS, John (1614–1672)

An Essay Towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language

London: Samuel Gellibrand, John Martyn, 1668

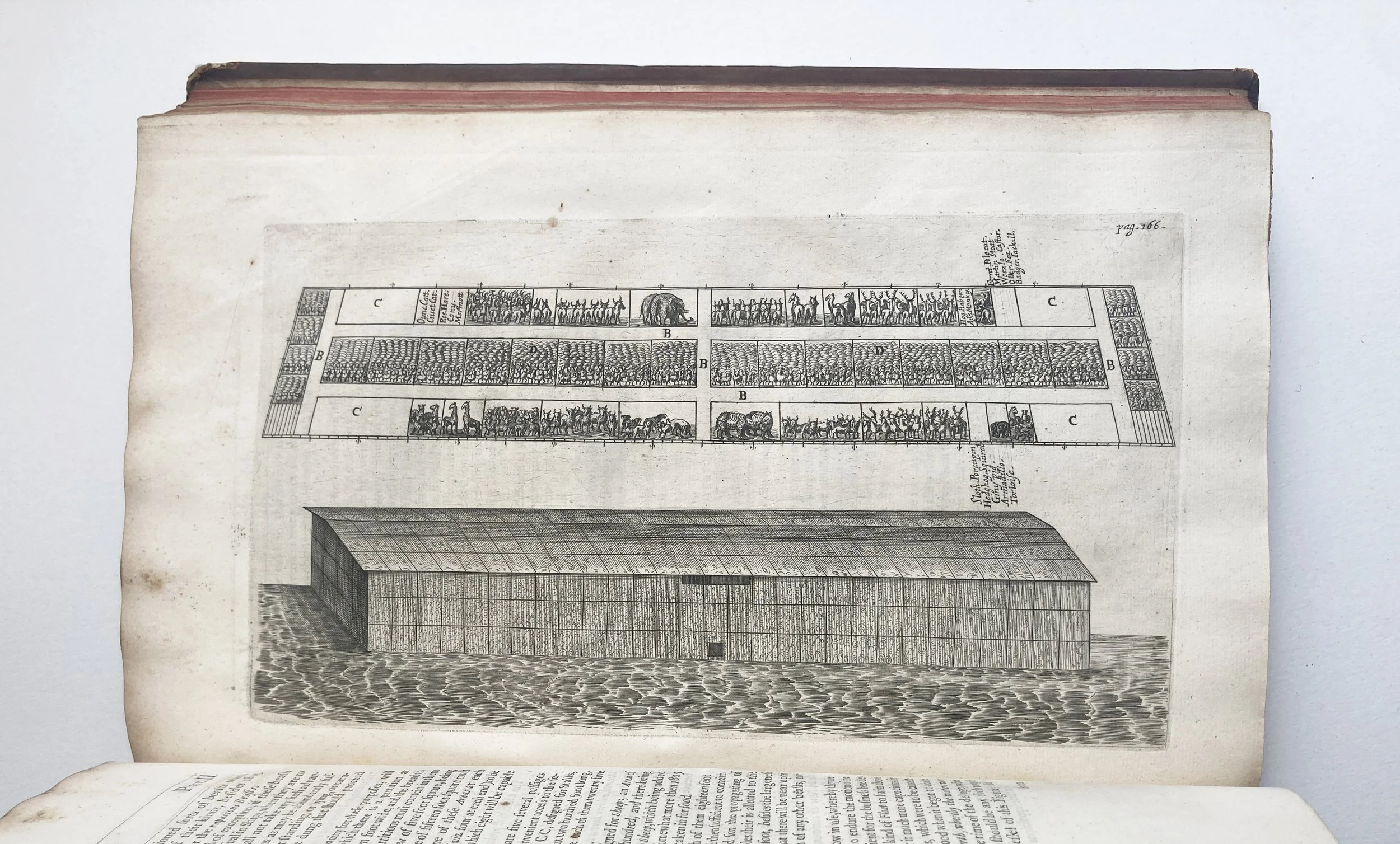

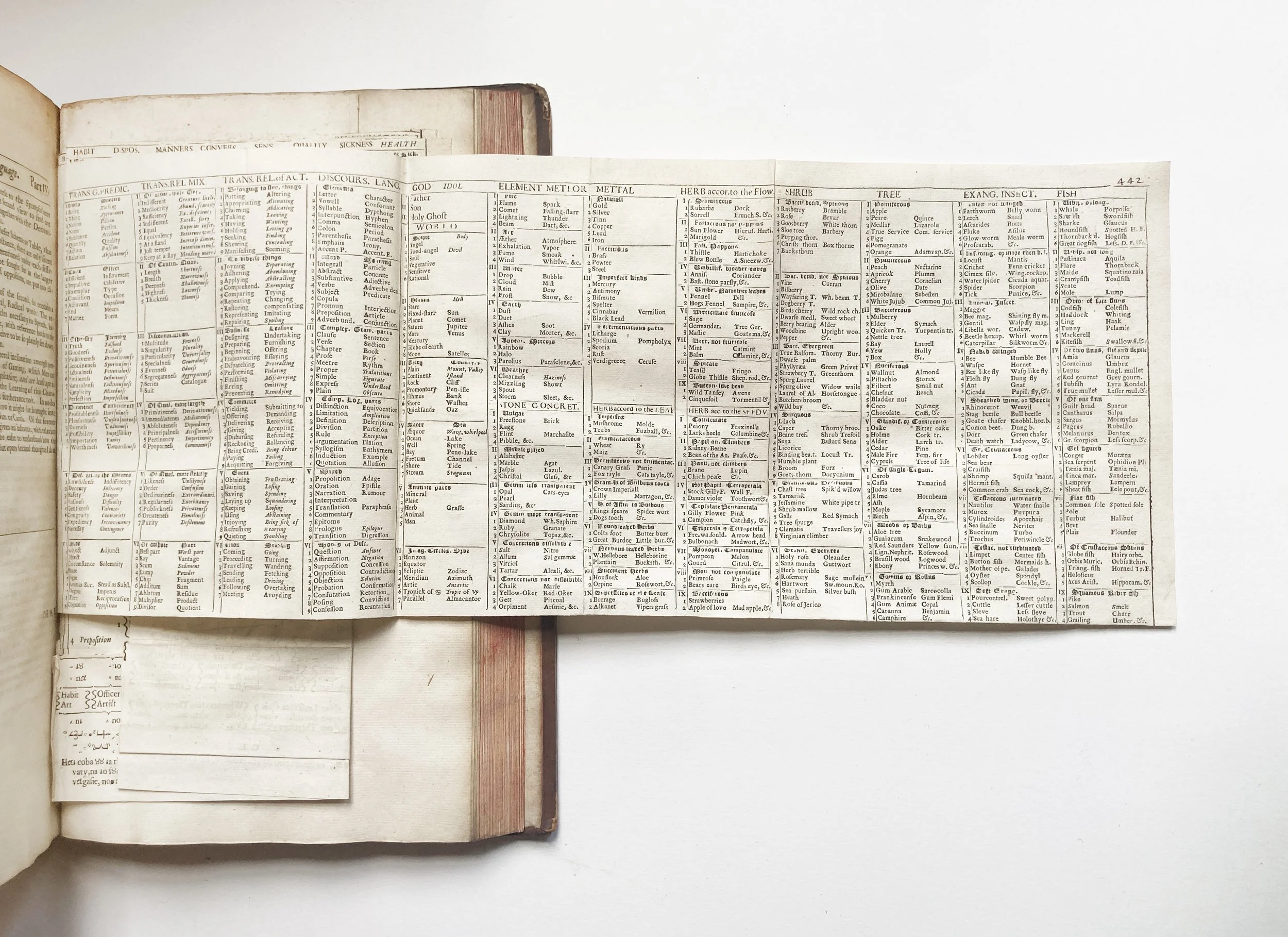

Folio, large paper copy; 374 x 242mm (page height 366mm); pp: [2] blank/order, [2] t.p./blank, [16], 1-454; + 79 leaves of Dictionary, unpaginated (158 pages); Illustrations: folding plates before pp. 167, 187, and two folding plates before p. 443.

Collation: π2 a-d2 B-Z4 Aa-Zz4 Aaa-Mmm4 aaa4 Aaa-Tttt4

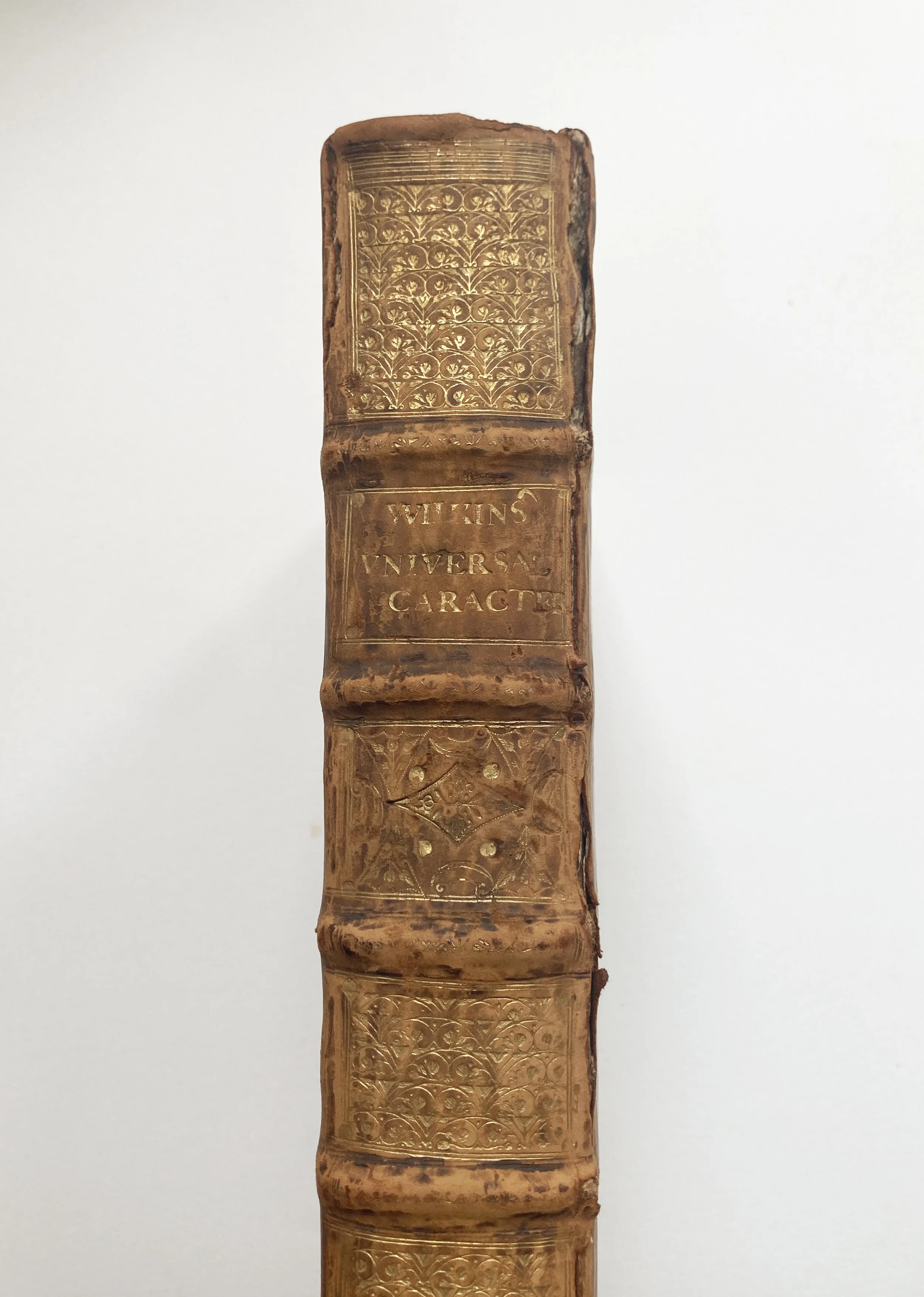

Full speckled calf, later polished calf spine with raised bands, double fillet ruled gilt compartments, crimson label with gilt lettering, margins sprinkled red. Text block in exceptional condition; clean, unmarked and amost untouched throughout; very slight mis-folding to the larger folding plates but again much better than usual; binding generally good but the front hinge weak and the leather cracked; spine worn; covers scuffed and edges bumped

A fine large-paper copy of John Wilkins’ famous Essay Towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language, which offers a universal classification system, linked to a new language and notation (‘character’):

Calls for a universal language had increased as a result of the flourishing of vernacular literature and an increasing dissatisfaction with Latin, partly with regard to the difficulty of learning it, but also with regard to its ambiguities and complexities. The vocabulary of this new language was to be built up by systematic modifications of the basic generic terms that were deemed to cover all the major categories of existence. A knowledge of the system would enable the reader, or listener, not just to recognize the signification of a word but also to understand how the referent fitted into the entire scheme of things. This is what made Wilkins’s artificial language ‘philosophical’, not just universal in the sense that a unanimously agreed upon lingua franca would be. (DNB)

Large-paper copies of the Essay are very rare, with only six auction records, and none since 1986 (Rare Book Hub).

Wilkins was Bishop of Chester, and was a founder member of the Royal Society. He studied at New Inn Hall and then Magdalen Hall, Oxford, and became Warden of Wadham College. During the interregnum Wilkins was at the centre of the Oxford Philosophical Club, a precursor of the Royal Society, and the immediate ancestor of the Oxford Philosophical Society. His interests ranged widely, and he was an important writer on natural theology. The Essay is his most celebrated work, and its project, of a universal language, was one of the major early concerns of the Royal Society.

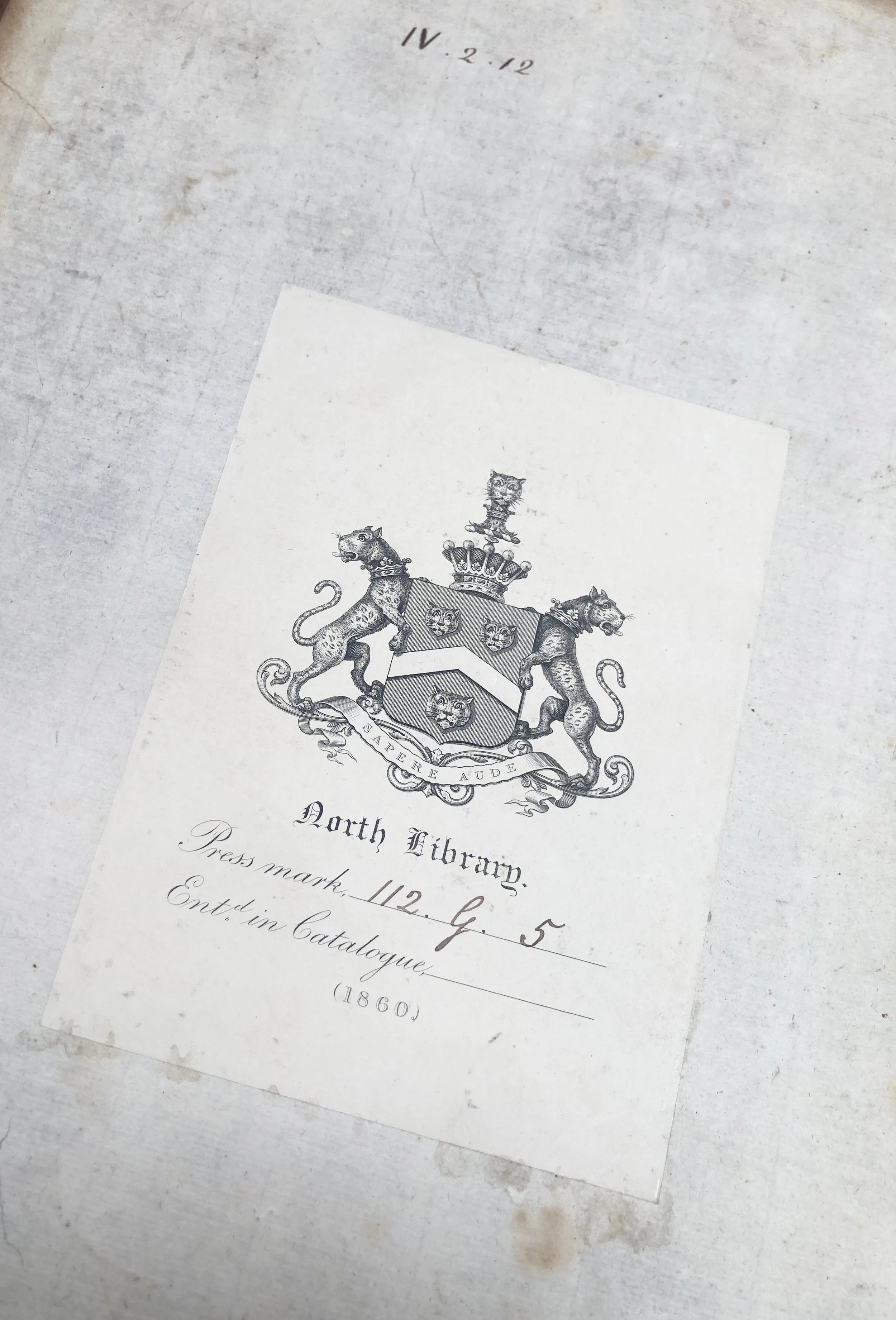

The present copy comes from the famous Macclesfield Library, amassed at Shirburn Castle by successive Earls of Macclesfield through the eighteenth century. Although post-dating the foundation of the Royal Society, the collection has very close links to its early members, as most of the early works are thought to have come from the working collection of John Collins (1625–1683), who acted as intermediary for a large number of mathematicians and natural philosophers, and wrote extensively on practical mathematics himself.

Intriguingly, the text-block is partially decorated with ochre to the page edges, and this has apparently been used to pick out the section of the book titled ‘Concerning Natural Grammar’, and the dictionary that makes up the final section of the book. This unusual and highly functional decoration may be another clue to the book’s original or at least most energetic owner.